Comparing germination curves for different seed lots

17 July, 2019

Introduction

Seed scientists are often faced with seed lots showing different germination behaviours. For instance, they can have different plant species, or one single plant species submitted to different treatments, e.g. different temperatures, different light conditions, different types of priming. One typical question is: how do I compare the germination behaviour of these different seed lots?

Let’s take a practical approach and start from an appropriate example: a few years ago, some collegues studied the germination behaviour for seeds of a plant species (Verbascum arcturus, BTW…), in different conditions. In detail, they considered the factorial combinations of two storage periods (LONG and SHORT storage) and two temperature regimes (FIX: constant daily temperature of 20°C; ALT: alternating daily temperature regime, with 25°C during daytime and 15°C during night time, with a 12:12h photoperiod). If you are not a seed scientist you may wonder why my colleagues made such an assay; well, there is evidence that, for some plant species, the germination ability improves over time after maturation. There is also evidence that some seeds may not germinate if they do not experience a daily temperature fluctuation. These are all mechanisms by which seeds can recognise that they are in favourable conditions (e.g. they are close to the soil surface), so that the chances for plant establishment are maximised. Clever, isn’t it? My colleagues wanted to discover whether this was the case for Verbascum.

Let’s go back to our assay: the experimental design consisted of four combinations (LONG-FIX, LONG-ALT, SHORT-FIX and SHORT-ALT) and four replicates for each combination. One replicate consisted of a Petri dish, that is a small plastic box containing humid blotting paper, with 25 seeds of Verbascum. In all, there were 16 Petri dishes, put in climatic chambers with the appropriate conditions. During the assay, my collegues made daily inspections: germinated seeds were counted and removed from the dishes. Inspections were made for 15 days, until no more germinations could be observed.

The dataset is available from a gitHub repository: let’s load it and have a look.

dataset <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/OnofriAndreaPG/agroBioData/master/TempStorage.csv", header = T, check.names = F)

head(dataset)

## Dish Storage Temp 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

## 1 1 Low Fix 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 4 6 0 1 0 3

## 2 2 Low Fix 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 2 7 2 3 0 5 1

## 3 3 Low Fix 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 3 5 2 4 0 1 3

## 4 4 Low Fix 0 0 0 0 1 0 3 0 0 3 1 1 0 4 4

## 5 5 High Fix 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 5 4 2 3 0

## 6 6 High Fix 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 7 8 1 2 1We have one row per Petri dish; the first three columns show dish id, storage and temperature conditions. The next 15 columns represent the inspection times (from 1 to 15) and contain the counts of germinated seeds. The research question is:

Is germination behaviour affected by storage and temperature conditions?

Response feature analyses

One possible line of attack is to take a summary measure for each dish, e.g. the total number of germinated seeds. Taking a single value for each dish brings us back to more common methods of data analysis: for example, we can fit some sort of GLM to test the significance of effects (storage, temperature and their interaction), within a fully factorial design. This is the typical way of fitting germination models in two-steps, which will be considered in the next section.

In this page we will consider the entire time series (from 1 to 15 days) and not only one single summary measure per Petri dish. The proposed solution will be based on the time-to-event platform, which has shown very useful and appropriate for seed germination studies (Onofri et al., 2011; Ritz et al., 2013; Onofri et al., 2019).

The germination time-course

It is necessary to re-organise the dataset in a more useful way. A good format can be obtained by using the ‘makeDrm()’ function in the ‘drcSeedGerm’ package, which can be installed from gitHub (see the code at: this link). The function needs to receive a dataframe storing the counts (dataset[,4:18]), a dataframe storing the factor variables (dataset[,2:3]), a vector with the number of seeds in each Petri dish (rep(25, 16)) and a vector of monitoring times.

library(drcSeedGerm)

datasetR <- makeDrm(dataset[,4:18], dataset[,2:3], rep(25, 16), 1:15)

head(datasetR, 16)

## Storage Temp Dish timeBef timeAf count nCum propCum

## 1 Low Fix 1 0 1 0 0 0.00

## 1.1 Low Fix 1 1 2 0 0 0.00

## 1.2 Low Fix 1 2 3 0 0 0.00

## 1.3 Low Fix 1 3 4 0 0 0.00

## 1.4 Low Fix 1 4 5 0 0 0.00

## 1.5 Low Fix 1 5 6 0 0 0.00

## 1.6 Low Fix 1 6 7 0 0 0.00

## 1.7 Low Fix 1 7 8 0 0 0.00

## 1.8 Low Fix 1 8 9 3 3 0.12

## 1.9 Low Fix 1 9 10 4 7 0.28

## 1.10 Low Fix 1 10 11 6 13 0.52

## 1.11 Low Fix 1 11 12 0 13 0.52

## 1.12 Low Fix 1 12 13 1 14 0.56

## 1.13 Low Fix 1 13 14 0 14 0.56

## 1.14 Low Fix 1 14 15 3 17 0.68

## 1.15 Low Fix 1 15 Inf 8 NA NAThe snippet above shows the first dish. The column ‘timeAf’ contains the time when the inspection was made and the column ‘count’ contains the number of germinated seeds (e.g. 9 seeds were counted at day 9). These seeds did not germinate exactly at day 9; they germinated within the interval between two inspections, that is between day 8 and day 9. The beginning of the interval is given in the variable ‘timeBef’. Apart from these columns, we have additional columns, which we are not going to use for our analyses. The cumulative counts of germinated seeds are in the column ‘nCum’; these cumulative counts have been converted into cumulative proportions by dividing by 25 (i.e., the total number of seeds in a dish; see the column ‘propCum’).

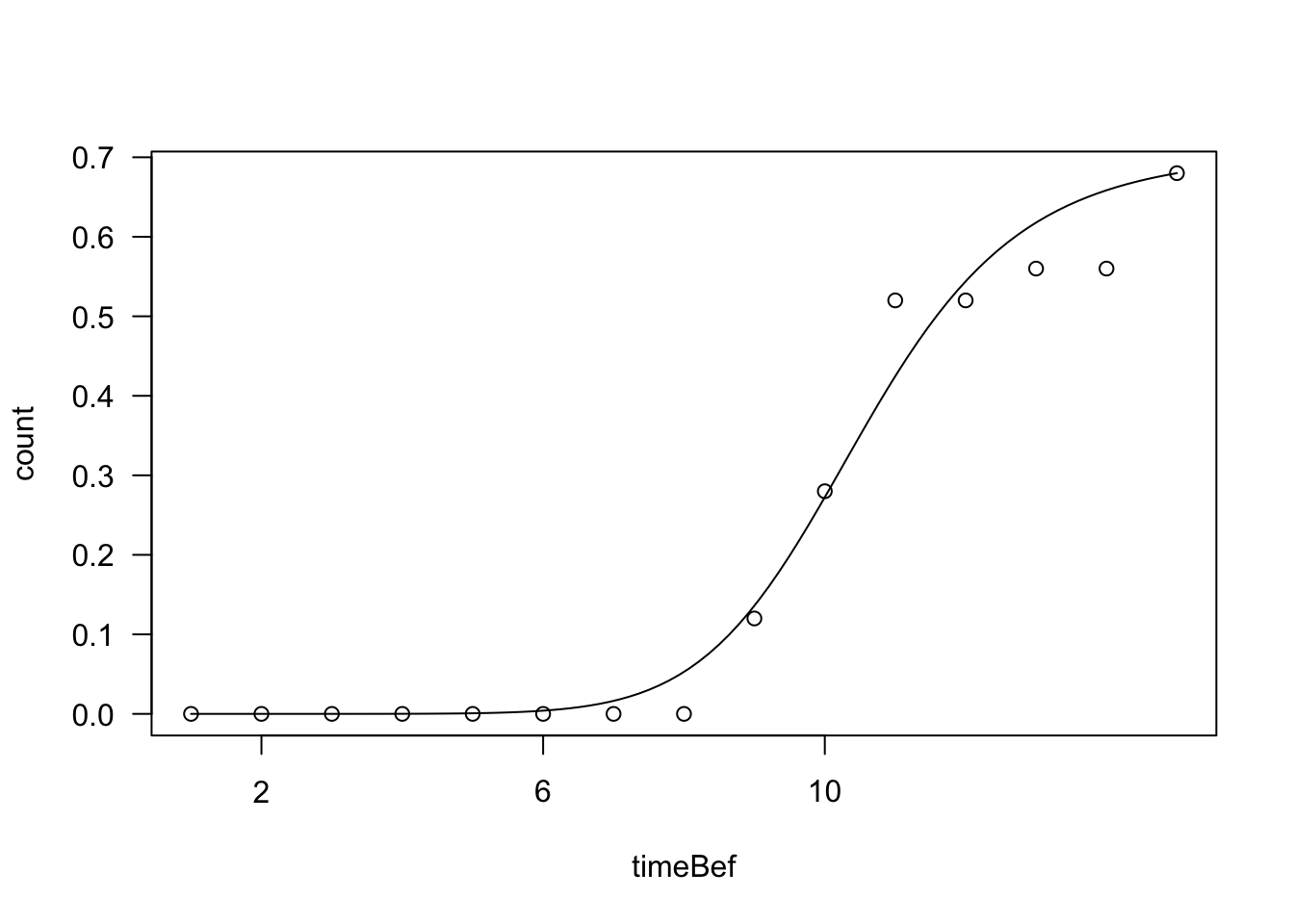

We can use a time-to-event model to parameterise the germination time-course for this dish. This is easily done by using the ‘drm()’ function in the ‘drc’ package (Ritz et al., 2013):

modPre <- drm(count ~ timeBef + timeAf, fct = LL.3(), data = datasetR,

type = "event", subset = c(Dish == 1))

plot(modPre, log = "")

Please, note the following:

- we are using the counts (‘count’) as the dependent variable

- as the independent variable: we are using the extremes of the inspection interval, within which germinations were observed (~ timeBef + time Af)

- we have assumed a log-logistic distribution of germination times (fct = LL.3()). A three parameter model is necessary, because there is a final fraction of ungerminated seeds (truncated distribution)

- we have set the argument ‘type = “event”’. Indeed, we are fitting a time-to-event model, not a nonlinear regression model, which would be incorrect, in this setting (see this link here ).

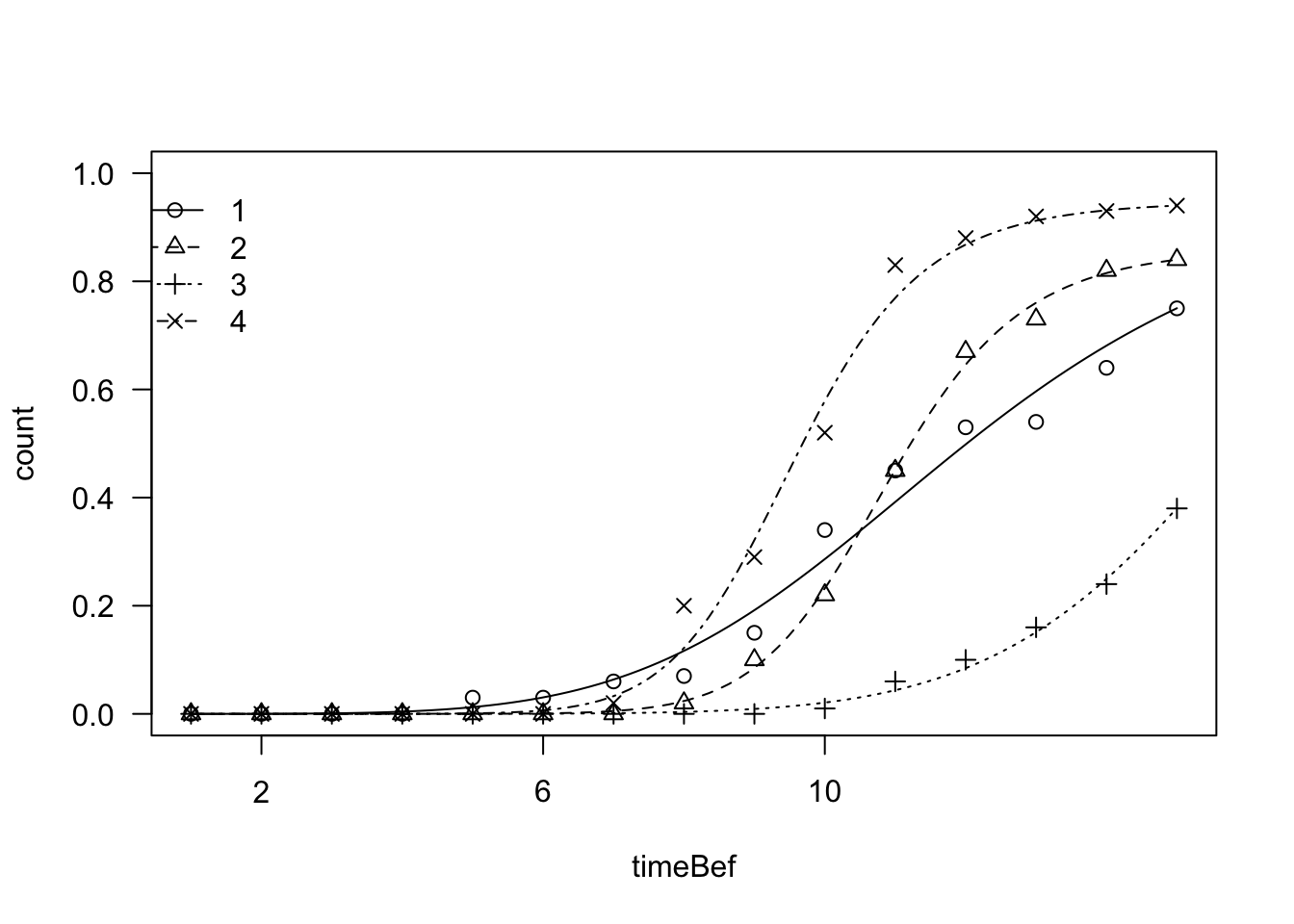

As we have determined the germination time-course for dish 1, we can do the same for all dishes. However, we have to instruct ‘drm()’ to define a different curve for each combination of storage and temperature. It is necessary to make an appropriate use of the ‘curveid’ argument. Please, see below.

comb <- factor(datasetR$Temp):factor(datasetR$Storage)

mod1 <- drm(count ~ timeBef + timeAf, fct = LL.3(), data = datasetR,

type = "event", curveid = comb)

plot(mod1, log = "", legendPos = c(2, 1))

It appears that there are visible differences between the curves (the legend considers the curves in alphabetical order, i.e. 1: Fix-Low, 2: Fix-High, 3: Alt-Low and 4: Alt-High). We can test that the curves are similar by coding a reduced model, where we have only one pooled curve for all treatment levels. It is enough to remove the ‘curveid’ argument.

modNull <- drm(count ~ timeBef + timeAf, fct = LL.3(), data = datasetR,

type = "event")

anova(mod1, modNull, test = "Chisq")

##

## 1st model

## fct: LL.3()

## pmodels: comb (for all parameters)

## 2nd model

## fct: LL.3()

## pmodels: 1 (for all parameters)

## ANOVA-like table

##

## ModelDf Loglik Df LR value p value

## 1st model 244 -753.54

## 2nd model 253 -854.93 9 202.77 0Now, we can compare the full model (four curves) with the reduced model (one common curve) by using a Likelihood Ratio Test, which is approximately distributed as a Chi-square. The test is highly significant. Of course, we can also test some other hypotheses. For example, we can code a model with different curves for storage times, assuming that the effect of temperature is irrelevant:

mod2 <- drm(count ~ timeBef + timeAf, fct = LL.3(), data = datasetR,

type = "event", curveid = Storage)

anova(mod1, mod2, test = "Chisq")

##

## 1st model

## fct: LL.3()

## pmodels: comb (for all parameters)

## 2nd model

## fct: LL.3()

## pmodels: Storage (for all parameters)

## ANOVA-like table

##

## ModelDf Loglik Df LR value p value

## 1st model 244 -753.54

## 2nd model 250 -797.26 6 87.436 0We see that the effect of temperature is significant. Similarly, we can test the effect of storage:

mod3 <- drm(count ~ timeBef + timeAf, fct = LL.3(), data = datasetR,

type = "event", curveid = Temp)

anova(mod1, mod3, test = "Chisq")

##

## 1st model

## fct: LL.3()

## pmodels: comb (for all parameters)

## 2nd model

## fct: LL.3()

## pmodels: Temp (for all parameters)

## ANOVA-like table

##

## ModelDf Loglik Df LR value p value

## 1st model 244 -753.54

## 2nd model 250 -849.48 6 191.87 0Again, we get significant results. So, we need to conclude that temperature and storage time changed the germination behavior of Verbascum.

Before concluding, it is necessary to mention that, in general, the above LR tests shoul be taken with care: the results are only approximate and the observed data are not totally independent, as multiple observations are taken in each experimental unit. It is not easy to include random effects in a time-to-event framework (Onofri et al., 2019); furthermore, we got very low p-levels, which leaves us very confident about the significance of effects. It may be a good suggestion, in general, to avoid formal hypothesis testing and compare the models by using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC: the lowest is the best), which confirms that the complete model with four curves is indeed the best one.

AIC(mod1, mod2, mod3, modNull)

## df AIC

## mod1 244 1995.088

## mod2 250 2094.524

## mod3 250 2198.961

## modNull 253 2215.862For those who are familiar with linear model parameterisation, it is possible to reach even a higher degree of flexibility by using the ‘pmodels’ argument, within the ‘drm()’ function. However, this will require another post. Thanks for reading!

References

- Onofri, A., Mesgaran, M.B., Tei, F., Cousens, R.D., 2011. The cure model: an improved way to describe seed germination? Weed Research 51, 516–524.

- Onofri, A., Piepho, H.-P., Kozak, M., 2019. Analysing censored data in agricultural research: A review with examples and software tips. Annals of Applied Biology 174, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/aab.12477

- Ritz, C., Pipper, C.B., Streibig, J.C., 2013. Analysis of germination data from agricultural experiments. European Journal of Agronomy 45, 1–6.